Elite paddlers and rowers have always known that race tactics can make the difference between standing on the podium and watching from the sidelines. A groundbreaking study by researchers Joshua A. Goreham, Scott C. Landry, John W. Kozey, Bruce Smith, and Michel Ladouceur from Dalhousie University and Acadia University has now provided unprecedented insights into the pacing strategies that separate champions from the rest of the field. Using advanced GPS technology and statistical analysis, their research examined the velocity patterns of elite canoe kayak sprint athletes during major international competitions, including the 2016 Olympics, World Cups, and 2017 World Championships.

What makes this study particularly valuable for athletes and coaches is its use of high-resolution GPS data collected every 10 meters throughout entire races, rather than traditional split times measured at 250-meter intervals. The researchers employed Principal Component Analysis (PCA), a sophisticated statistical method that can identify subtle patterns in racing data that might be invisible to conventional analysis. As the study notes, “these time-series data, combined with new data analysis methods, have the potential to aid performance analysts to compare pacing strategies from multiple athletes within- or between-races.” For paddlers and rowers seeking to optimize their race execution, this represents a quantum leap in understanding how elite athletes distribute their energy across different race distances.

Race Distance Determines Your Strategy

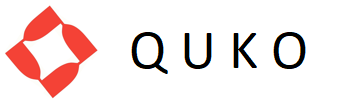

The research reveals that successful pacing strategies are fundamentally tied to race distance, with each distance category requiring a distinctly different approach. For 200-meter sprint events, elite athletes consistently employ what researchers call an “all-out pacing strategy.” This involves “quick acceleration followed by trying to maintain high-power output for as long as possible” and is characterized by athletes spending approximately 25-35% of the race in the acceleration phase before experiencing a gradual decrease in velocity. The timing of this strategy aligns perfectly with the depletion of anaerobically-created energy stores, typically occurring around 10 seconds into the race.

Figure 2 from the cited paper. Average normalised velocity for the Top 3 (wide solid line) and Bottom 3 (wide dashed line) athletes for 200 m (Panel a), 500 m (Panel B), and 1000 m (Panel C) races. Dotted line, race average. ± one standard deviation shown in thin solid line (Top 3) and thin dashed line (Bottom 3).

Figure 2 from the cited paper. Average normalised velocity for the Top 3 (wide solid line) and Bottom 3 (wide dashed line) athletes for 200 m (Panel a), 500 m (Panel B), and 1000 m (Panel C) races. Dotted line, race average. ± one standard deviation shown in thin solid line (Top 3) and thin dashed line (Bottom 3).

As race distance increases to 500 meters, the optimal strategy shifts to a “positive pacing strategy” where athletes achieve maximum velocity early in the race and then experience “a slow and steady reduction in velocity” throughout the remaining distance. This approach likely capitalizes on oxygen consumption kinetics benefits compared to other pacing strategies, allowing athletes to maintain a higher overall speed despite the gradual decline. The research found that both top performers and lower-ranked athletes reached their maximum velocity at virtually the same point in 500-meter races, suggesting that the acceleration phase timing is relatively standardized at this distance.

The most complex and tactically sophisticated racing occurs in 1000-meter events, where elite athletes adopt what the researchers term a “seahorse-shaped pacing strategy.” This pattern involves “a submaximal but relatively fast start which leads to a slower second 250 m split” followed by the slowest portion of the race in the third 250-meter segment, and finally “an end spurt and then a slight decay in velocity to finish the race.” This strategy requires exceptional race management skills, as athletes must carefully balance their energy expenditure across multiple phases while maintaining enough reserve capacity for a decisive finishing kick.

The Championship Difference: What Separates Winners from the Rest

Perhaps the most practically significant finding of this research concerns the differences between medallists (top 3 finishers) and non-medallists (bottom 3 finishers) across different race distances. Interestingly, the study found no significant differences in pacing patterns between these groups in 200-meter and 500-meter events, suggesting that in shorter races, raw speed and power output are the primary determinants of success rather than tactical execution. However, the picture changes dramatically in 1000-meter races, where strategic pacing becomes a crucial performance differentiator.

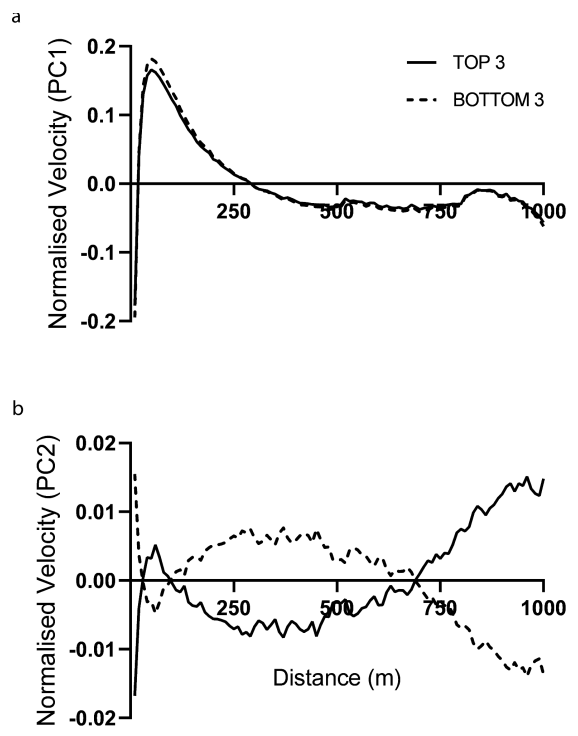

Figure 3 from the cited paper. Top 3 (solid line) and Bottom 3 (dashed line) average normalised velocity PC1 (magnitude) and PC2 (range feature) values for 1000 m races.

Figure 3 from the cited paper. Top 3 (solid line) and Bottom 3 (dashed line) average normalised velocity PC1 (magnitude) and PC2 (range feature) values for 1000 m races.

The statistical analysis revealed that medallists and non-medallists showed significant differences in two key pacing characteristics during 1000-meter races. First, non-medallists tended to expend excessive energy during the acceleration phase, with “Bottom 3 1000 m athletes increased their velocity more in the acceleration phase (i.e. first 100 m) than Top 3 athletes did in proportion to the remainder of their race.” This tactical error appears to compromise their ability to execute a strong finish, as the research demonstrates that successful athletes must maintain adequate energy reserves for the crucial final 300 meters of the race.

The second critical difference lies in the execution of the end spurt phase. The study found that “Top 3 athletes tend to have a similar pacing pattern as the Bottom 3 athletes with the addition of an end spurt phase starting at approximatively 700 m into the race.” In contrast, as non-medallists approached the 700-meter mark, “their velocity decreased rapidly, and no end spurt was present.” This finding has profound implications for training and race preparation, as it suggests that champions distinguish themselves not just through superior fitness, but through superior energy management and the ability to accelerate when fatigue is at its peak.

Practical Applications for Training and Competition

The implications of this research extend far beyond academic understanding and offer concrete guidance for athletes and coaches in both canoe/kayak sprint and rowing disciplines. The study’s use of high-resolution GPS data provides what the researchers call a “template” for developing optimal pacing strategies, moving beyond traditional split-time analysis that may miss crucial tactical nuances. For athletes competing in shorter events, the research confirms that maximizing acceleration and maintaining the highest possible velocity should be the primary focus, with tactical considerations playing a minimal role in performance outcomes.

For longer-distance competitors, however, the findings suggest that race preparation must include specific work on energy distribution and end-spurt capabilities. The research indicates that successful 1000-meter athletes must “have enough energy remaining to increase boat velocity late in the race for a strong end spurt phase.” This requires not just physical preparation but also the development of sophisticated race awareness and the ability to judge effort levels throughout different phases of the race. Training programs should therefore include race-specific simulations that teach athletes to avoid the common tactical error of excessive early-race energy expenditure.

The study’s methodology also highlights the value of modern GPS technology in performance analysis and training feedback. As the researchers note, “GPS provide information that can be used to better prepare athletes for canoe kayak sprint races lasting between 30 s and 240 s in duration.” For teams and individual athletes with access to similar technology, this suggests that detailed velocity analysis should become a standard part of training monitoring and competition preparation. The ability to analyze pacing patterns at 10-meter resolution rather than traditional 250-meter splits provides coaches with unprecedented insight into their athletes’ tactical execution and areas for improvement.

The research concludes that while pacing strategies may seem less critical in shorter events where “all elite competitors use an all-out pacing strategy, where the race winner is often the athlete who can reach the greatest velocity and maintain, or only slightly decline their velocity and power output for the race duration,” the tactical dimension becomes increasingly important as race distance increases. For athletes serious about reaching their competitive potential, understanding and practicing these evidence-based pacing strategies could be the difference between achieving personal goals and falling short when it matters most.

Goreham, J. A., Landry, S. C., Kozey, J. W., Smith, B., & Ladouceur, M. (2020). Using principal component analysis to investigate pacing strategies in elite international canoe kayak sprint races. Sports Biomechanics https://doi.org/10.1080/14763141.2020.1806348