Recent groundbreaking research from the University of Rennes has provided crucial insights into the physiological demands of Olympic kayaking distances that could revolutionize how paddlers and rowers approach their training. A comprehensive study by Zouhal and colleagues, published in the Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, examined the precise energy system contributions during 500-meter and 1000-meter flat water kayaking races using advanced field-based measurements with elite athletes.

Understanding how your body produces energy during racing is fundamental to optimizing performance, whether you’re powering through a sprint kayak race or pulling hard in a rowing event. The research team used a sophisticated method called accumulated oxygen deficit (AOD) to measure exactly how much energy comes from aerobic (with oxygen) versus anaerobic (without oxygen) pathways during actual race conditions on open water. Seven internationally ranked male kayakers, averaging 21.8 years old and competing at French national level, participated in this study that took place just weeks before the 2008 Olympic selection events.

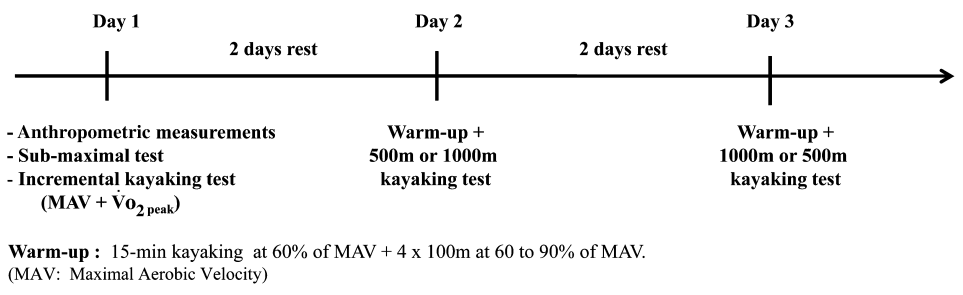

Figure 1 from the cited paper. Setup used in the experiment: incremental, 500- and 1,000-m kayaking tests.

Figure 1 from the cited paper. Setup used in the experiment: incremental, 500- and 1,000-m kayaking tests.

The Science Behind Peak Performance

The study revealed fascinating differences between the two Olympic distances that every serious paddler should understand. For the 500-meter distance, athletes derived “78.30% aerobic and 21.70% anaerobic” energy, while the 1000-meter race showed a significantly different energy profile with “86.61% aerobic and 13.38% anaerobic” contributions. This means that even the shorter, more explosive 500-meter race relies heavily on aerobic metabolism - much more than many athletes realize.

What makes this research particularly valuable is that it was conducted under real racing conditions rather than in a laboratory setting. The athletes used their own boats and competed against other elite paddlers to simulate actual race environments. Performance levels reached 95% and 94% of personal best times for the 500-meter and 1000-meter distances respectively, confirming that the physiological demands measured truly reflect competitive racing conditions.

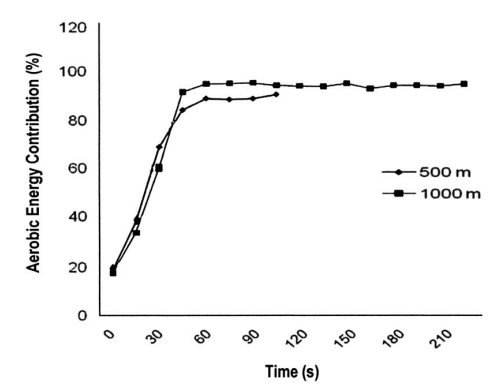

The timing of energy system transitions proves equally revealing. During both distances, anaerobic energy dominates the initial phase of the race, but the crossover point where aerobic metabolism becomes predominant occurs at approximately 30 seconds into the race. “During the first 45 seconds, the aerobic and anaerobic profiles were almost identical between the 2 kayaking races,” but after this critical period, the 1000-meter race becomes increasingly dependent on aerobic energy production.

Figure 2 from the cited paper. Aerobic energy contribution to the 500- and 1000-m kayaking, showing how aerobic contribution evolves throughout each race distance.

Figure 2 from the cited paper. Aerobic energy contribution to the 500- and 1000-m kayaking, showing how aerobic contribution evolves throughout each race distance.

Training Implications for Modern Athletes

These findings have profound implications for how paddlers and rowers should structure their training programs. The research demonstrates that “the 500- and 1,000-m races are 2 physiologically different kayaking events” requiring distinct preparation strategies. For athletes specializing in the 500-meter distance, the higher anaerobic contribution of 21.7% compared to 13.4% in the 1000-meter suggests that explosive power development and anaerobic capacity training deserve significant attention in their programs.

However, it’s crucial to recognize that even the 500-meter race, despite being the shorter and more explosive distance, still derives nearly 80% of its energy from aerobic metabolism. This means that building a robust aerobic base remains essential even for sprint specialists. The study’s authors conclude that “training prescription for elite athletes should emphasize aerobic high-intensity training for the 1,000 m and anaerobic short-term training for the 500-m race,” but this doesn’t mean neglecting either energy system entirely.

The research also revealed that blood lactate concentrations were significantly higher after 500-meter races compared to 1000-meter efforts, reaching 18.2 versus 14.4 millimoles per liter respectively. This biochemical evidence supports the greater reliance on anaerobic glycolysis during the shorter distance and reinforces the need for lactate tolerance training in sprint-focused programs.

For rowing athletes, these findings translate directly despite the different sport context. The physiological demands of producing power over similar time domains remain consistent whether you’re wielding a paddle or pulling oars. A 500-meter kayak race averaging 108 seconds mirrors closely the demands of a 500-meter rowing sprint, while 1000-meter efforts in both sports require similar energy system contributions over their 3-4 minute durations.

Revolutionizing Periodization and Performance

The research challenges traditional assumptions about sprint training and suggests a more nuanced approach to energy system development. Rather than viewing 500-meter and 1000-meter training as simply different intensities of the same physiological demand, coaches and athletes should recognize them as fundamentally different events requiring specialized preparation.

The study found that athletes reached speeds of 107% and 102% of their maximal aerobic velocity during 500-meter and 1000-meter races respectively. This data provides concrete targets for training prescription - athletes preparing for 500-meter events need to develop the capacity to sustain efforts significantly above their aerobic threshold, while 1000-meter specialists require the ability to maintain pace closer to their maximal aerobic power for extended periods.

Modern technology now allows athletes to monitor these energy system contributions during training using heart rate variability, lactate testing, and power measurement tools. By understanding the precise physiological demands revealed in this research, athletes can use training data to ensure their preparation matches the energy system requirements they’ll face in competition. The crossover point at 30 seconds also provides a valuable benchmark for structuring interval training and pacing strategies.

The practical applications extend beyond just training prescription. Race strategy development benefits enormously from understanding when aerobic metabolism becomes dominant and how energy system contributions evolve throughout each distance. Athletes can optimize their start strategies knowing that the first 30 seconds rely heavily on anaerobic power, then shift their focus to sustaining aerobic output as the race progresses.

Zouhal, H., Le Douairon Lahaye, S., Ben Abderrahaman, A., Minter, G., Herbez, R., & Castagna, C. (2012). Energy system contribution to Olympic distances in flat water kayaking (500 and 1,000 m) in highly trained subjects. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 26(3), 825-831.