Recent groundbreaking research by Michael Kellmann and Klaus-Dietrich Günther from the Institut für Sportwissenschaft at Universität Potsdam and the German Rowing Association has revealed crucial insights into how elite athletes experience stress and recovery during high-intensity training preparation. Their study, published in Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, followed eleven elite rowers from the German National Rowing Team as they prepared for the 1996 Atlanta Olympic Games, providing valuable lessons that extend beyond rowing to all paddling sports including sprint kayaking and canoeing.

The Science Behind Training Load and Athletic Wellbeing

The relationship between training intensity and an athlete’s physical and mental state is more complex than simply “train harder, get stronger.” The German research team discovered what they termed a “dose-response relationship” between training volume and the subjective assessment of stress and recovery in elite athletes. This means that as training load increases, athletes experience predictable changes in how their bodies and minds respond to the demands placed upon them.

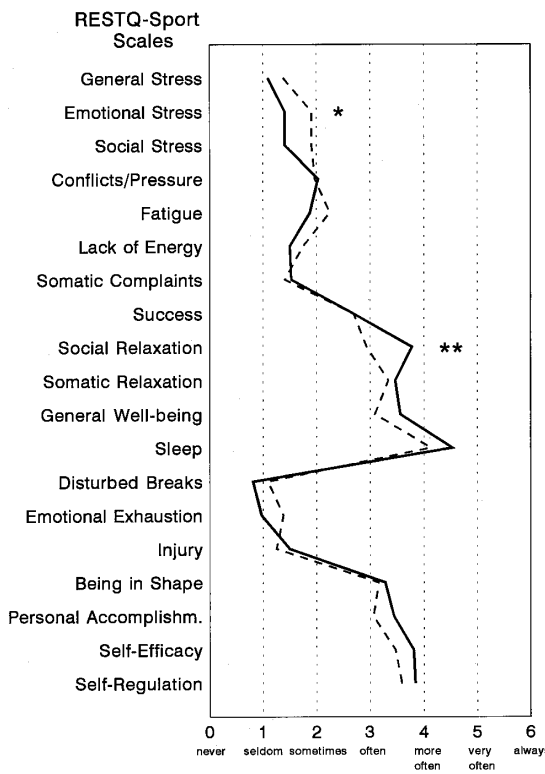

“The average number of minutes of daily extensive endurance training mirrored the trend for Somatic Complaints,” the researchers observed. When extensive endurance training reached its peak during the preparation camp, athletes reported the highest levels of physical complaints, lack of energy, and fitness-related injuries. Conversely, when training volume decreased as competition approached, these stress indicators also decreased while recovery markers improved.

Figure 1 from the cited paper: Means and standard deviations of the RESTQ-Sport scale Somatic Complaints and the average length of daily extensive endurance training throughout the training camp.

Figure 1 from the cited paper: Means and standard deviations of the RESTQ-Sport scale Somatic Complaints and the average length of daily extensive endurance training throughout the training camp.

This pattern is particularly relevant for paddling athletes who undergo similar periodized training cycles. Whether you’re preparing for sprint kayaking championships or canoeing competitions, understanding that your body’s stress responses will naturally fluctuate with training load can help normalize the physical and mental challenges you experience during intense preparation phases.

Understanding the Multiple Dimensions of Stress and Recovery

One of the most significant findings from this research challenges the common misconception that recovery is simply the absence of stress. The study utilized the Recovery-Stress-Questionnaire for Athletes (RESTQ-Sport), which measures both stress-related experiences and recovery-associated activities across multiple dimensions of athletic life.

“Recovery encompasses active processes of reestablishing psychological and physical resources and states that allow the taxing of these resources again,” the researchers explain. This means that effective recovery requires intentional activities and strategies, not just passive rest. The questionnaire revealed that athletes experience stress and recovery on several levels: physical (somatic), emotional, social, and performance-related.

For paddling athletes, this multi-dimensional understanding is crucial because your sport demands not only physical endurance but also technical precision, tactical awareness, and mental resilience. The research showed that different aspects of stress and recovery follow distinct patterns. While physical complaints peaked with high training loads, social aspects of recovery could be enhanced through team-building activities and increased social interaction during training camps.

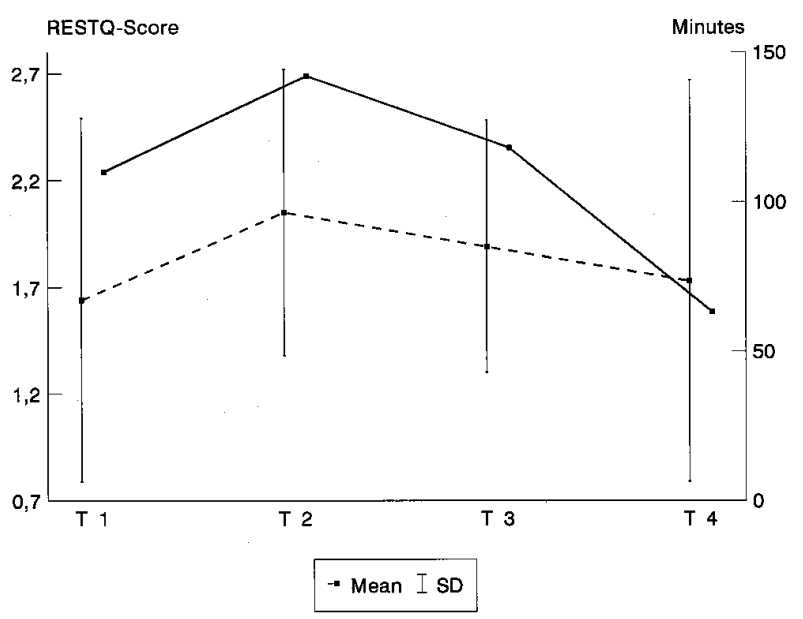

Figure 2 from the cited paper: Means and standard deviations of the RESTQ-Sport scale Fitness/Being in Shape and the average length of daily extensive endurance training throughout the training camp.

Figure 2 from the cited paper: Means and standard deviations of the RESTQ-Sport scale Fitness/Being in Shape and the average length of daily extensive endurance training throughout the training camp.

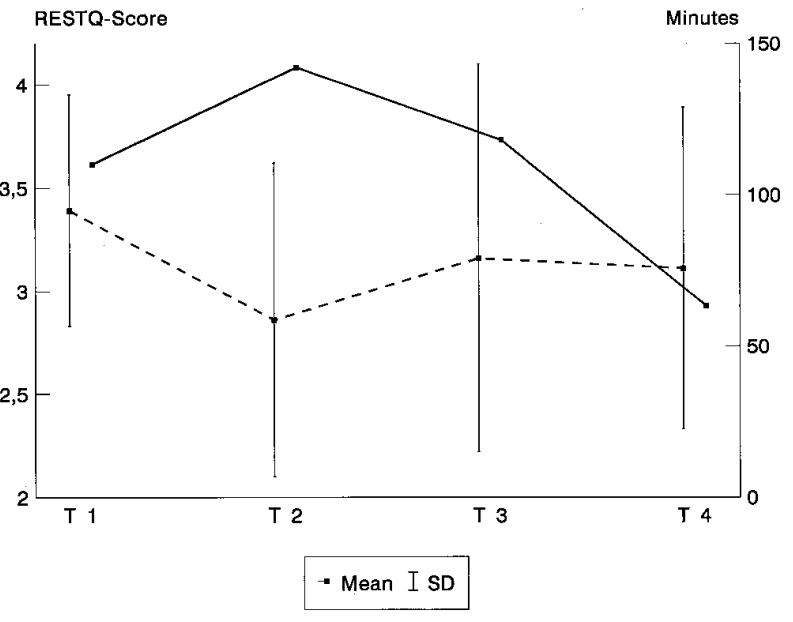

The study also revealed that as major competitions approached, athletes experienced increased emotional stress and decreased social relaxation. “The differences in the scales Emotional Stress and Social Relaxation turned out to be significant” when comparing athletes’ states during training camp versus two days before their Olympic preliminaries. This finding suggests that the psychological pressure of competition affects athletes beyond just physical preparation.

Practical Applications for Monitoring and Optimization

The research provides concrete evidence for the importance of systematic monitoring in elite sport preparation. The scientists discovered that asking athletes simple questions about their recent experiences – what happened in the past three days – provided valuable insights into their stress-recovery balance. “Basically the RESTQ-Sport asks the question: What happened in the past 3 days/nights?” This approach gives coaches and athletes specific starting points for intervention rather than just assessing current mood states.

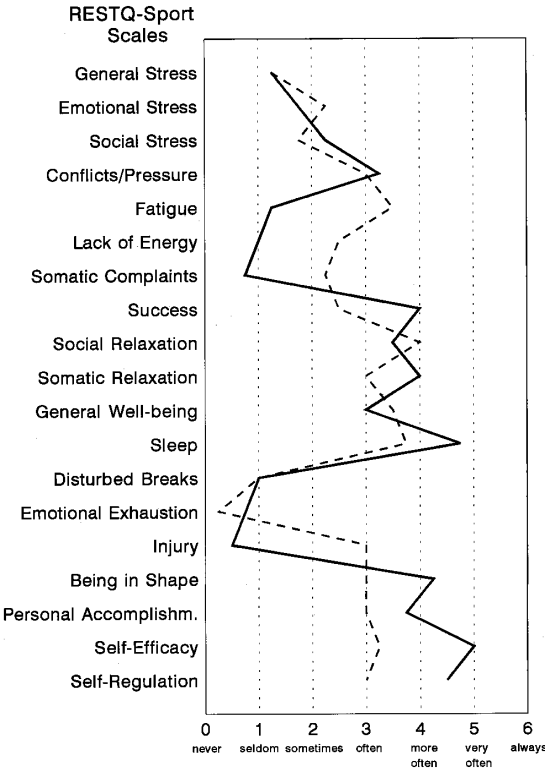

The study’s comparison of two individual athletes demonstrates the practical value of this monitoring approach. Rower A, whose boat won the only medal from this sample, showed “a more positive recovery-stress state indicated by lower scores of Fatigue, Lack of Energy, and Somatic Complaints, as well as higher scores of Fitness/Being in Shape, Burnout/Personal Accomplishment, Self-Efficacy, and Self-Regulation” compared to Rower B, whose boat finished 13th. This difference was measurable nine days before the finals, suggesting that stress-recovery monitoring could potentially predict performance outcomes.

Figure 4 from the cited paper: RESTQ-Sport profiles for rower A (solid line) and rower B (broken line) 2 days before preliminaries.

Figure 4 from the cited paper: RESTQ-Sport profiles for rower A (solid line) and rower B (broken line) 2 days before preliminaries.

For paddling athletes and their support teams, this research emphasizes that effective training monitoring should extend beyond traditional physiological markers like heart rate, lactate levels, or power output. The psychological and social dimensions of athlete preparation are equally important and can be systematically tracked. The knowledge that “recovery is an active process to reestablish psychological and physical resources” empowers athletes to take greater responsibility for their own recovery strategies, whether through social activities, mental training, or specific physical recovery protocols.

The findings also highlight the importance of timing in competitive preparation. The researchers noted that “adequate recovery during phases of intensive training prevent athletes from overtraining.” This suggests that monitoring stress-recovery balance becomes even more critical during the most demanding phases of training, when the natural tendency might be to focus solely on physical adaptation while neglecting the psychological and social aspects of athlete wellbeing.

Understanding these patterns can help paddling athletes and coaches make more informed decisions about training adjustments, competition preparation, and intervention strategies. Whether you’re a sprint kayaker fine-tuning your preparation for nationals or a canoeist working toward international competition, recognizing that your stress and recovery responses follow predictable patterns can help you optimize both your training process and competitive performance.

Reference: Kellmann, M., & Günther, K-D. (2000). Changes in stress and recovery in elite rowers during preparation for the Olympic Games. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 32(3), 676-683.