Every stroke you take on the water represents a transfer of energy from your muscles to forward motion, but how much of that precious energy actually propels you forward? Research conducted by K. Affeld, K. Schichl, and A. Ziemann from the Freie Universität Berlin and Technische Universität Berlin has revealed a startling truth about paddle sports: “Between one-fourth and one-third of the energy in rowing is lost to the flow of water around the blade which decreases efficiency.” This groundbreaking study not only quantifies these energy losses but also provides a practical method for measuring rowing efficiency in real-time, offering insights that extend far beyond traditional rowing to benefit athletes in sprint kayaking and canoeing as well.

Understanding Energy Loss in Paddle Sports

When you pull your paddle or oar through the water, you’re not just fighting against the water’s resistance - you’re creating a complex hydrodynamic environment around your blade. The researchers define hydrodynamic efficiency as “the quotient of the mechanical power the rower exerts to the power needed for the propulsion of the boat.” Think of it this way: if you could somehow make your blade perfectly efficient, every joule of energy you put into your stroke would translate directly into forward motion. In reality, a significant portion of your energy goes into creating vortices and turbulence in the water behind your blade - energy that’s lost forever to the wake.

This energy loss isn’t uniform throughout your stroke. The study reveals that efficiency varies dramatically based on the angle of your paddle and the phase of your stroke cycle. Unlike previous research that could only provide average efficiency values, this new methodology allows scientists and coaches to see exactly when and where energy is being wasted during each stroke. For sprint kayakers and canoeists, this concept is equally relevant - every time your paddle enters, moves through, and exits the water, the same hydrodynamic principles apply, making this research valuable across all paddle sports.

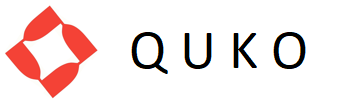

Figure 1 from the cited paper: The velocity of a single scull boat and of the center of gravity of the combined system rower boat (upper panel), and the power of the rower (lower panel). The pictographs show the position of the rower.

Figure 1 from the cited paper: The velocity of a single scull boat and of the center of gravity of the combined system rower boat (upper panel), and the power of the rower (lower panel). The pictographs show the position of the rower.

The Science of Blade Movement and Force Generation

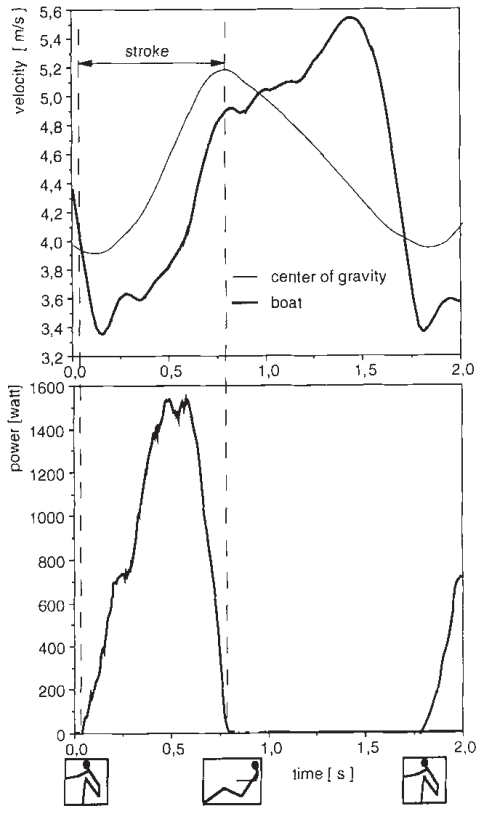

The breakthrough in this research comes from applying airfoil theory to paddle sports. Rather than trying to analyze the complex movement of the entire athlete-boat system, the researchers focused specifically on the blade itself, treating it like an airplane wing moving through water. This approach reveals that two distinct forces act on your blade during each stroke: drag and lift. The drag force acts parallel to the blade’s movement and represents energy that’s lost to the water, while the lift force acts perpendicular to the movement and can contribute to propulsion without energy loss.

What makes this particularly interesting for paddle sport athletes is the finding that “the drag forces contribute most to the propulsion of the boat.” This means that the very force that represents energy loss is also your primary source of forward motion. The key is optimizing the balance between useful drag that propels you forward and wasteful drag that simply heats up the water behind you. The research shows that this balance changes constantly throughout your stroke, with efficiency peaks occurring at the beginning and end of each stroke cycle, while the middle portion - when your paddle is perpendicular to your direction of travel - shows different efficiency characteristics.

Figure 2 from the cited paper: The path of the center point of the blade. The arrows indicate the lift and drag forces. Drag forces are parallel to the path and determine the power loss. Lift forces are perpendicular to the path and do not contribute to the power loss. Both forces, however, contribute to the propulsion according to their directions, which are different at each point of the blade path.

Figure 2 from the cited paper: The path of the center point of the blade. The arrows indicate the lift and drag forces. Drag forces are parallel to the path and determine the power loss. Lift forces are perpendicular to the path and do not contribute to the power loss. Both forces, however, contribute to the propulsion according to their directions, which are different at each point of the blade path.

Real-Time Efficiency Measurement and Stroke Analysis

The methodology developed by the researchers allows for continuous monitoring of efficiency throughout each stroke by measuring boat velocity, paddle angular velocity, and the moment exerted by the athlete. These parameters are “measured, digitized, and stored in the boat for later computation on shore.” For the first time, coaches and athletes can see exactly how efficiency varies during different phases of the stroke cycle, providing unprecedented insight into technique optimization.

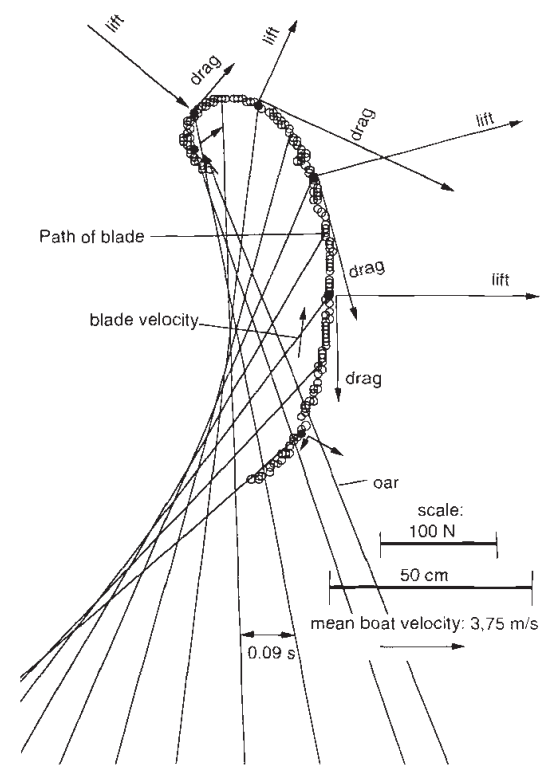

The results reveal fascinating patterns in how efficiency changes throughout a stroke. The study shows that while efficiency tends to peak at the beginning and end of the stroke cycle, these phases contribute relatively little to overall propulsion because power output is minimal at these extremes. The critical insight for athletes is understanding that “the power is utilized differently during the stroke” - maximum power typically occurs when the paddle is perpendicular to the boat’s direction, but this isn’t necessarily when efficiency is highest.

Perhaps most importantly for competitive athletes, the research demonstrates that efficiency is strongly correlated with boat velocity. As speed increases, mean efficiency also increases, creating a positive feedback loop where faster athletes not only move quicker but do so more efficiently. This finding has profound implications for training, suggesting that building the capacity to maintain higher speeds may improve not just performance but also energy economy.

Figure 3 from the cited paper: The rowing efficiency and power for one scull — half of the total power output — as a function of the rowing angle in a single scull. The comparison of the two curves gives an indication if a rowing style is effective.

Figure 3 from the cited paper: The rowing efficiency and power for one scull — half of the total power output — as a function of the rowing angle in a single scull. The comparison of the two curves gives an indication if a rowing style is effective.

Equipment Innovation and Performance Optimization

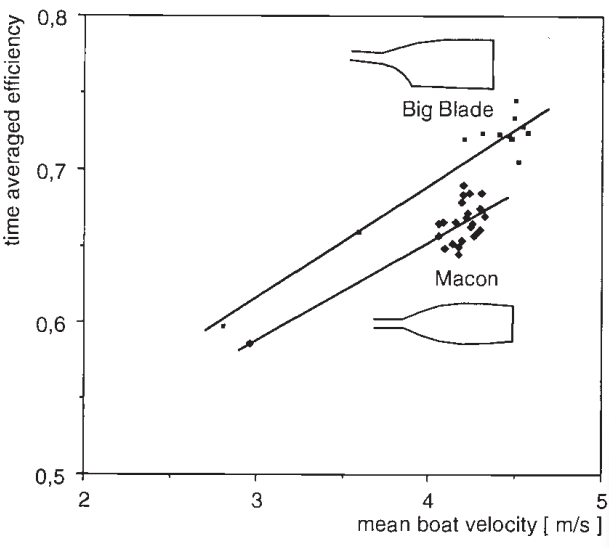

Beyond technique analysis, this research provides a scientific framework for evaluating equipment improvements. The study compared traditional Macon blades with newer “Big Blade” designs, finding that the larger blade area allowed the test subject to achieve approximately 3% higher efficiency. While 3% might seem modest, in elite competition where margins of victory are often measured in hundredths of seconds, such improvements can be decisive.

This equipment evaluation methodology has clear applications for sprint kayaking and canoeing, where paddle design continues to evolve. The ability to quantify efficiency improvements objectively removes much of the guesswork from equipment selection and development. Athletes and coaches can now move beyond subjective assessments of how a paddle “feels” to understand precisely how different blade shapes, sizes, and designs affect energy transfer efficiency.

The research also reveals that individual rowing style significantly influences efficiency patterns. The curves vary individually, “influenced by various movements the rower carries out to keep the balance and the boat’s position on the course.” This suggests that while general principles of efficiency apply across athletes, optimal technique may need to be individualized based on each athlete’s unique biomechanics and style preferences.

Figure 4 from the cited paper: For the evaluation of a blade the efficiency is calculated and averaged over one cycle. If one plots these values as a function of the mean boat velocity, a regression line can be computed and a comparison can be made.

Figure 4 from the cited paper: For the evaluation of a blade the efficiency is calculated and averaged over one cycle. If one plots these values as a function of the mean boat velocity, a regression line can be computed and a comparison can be made.

The implications of this research extend far beyond the laboratory. By providing “a practical tool for evaluation of rowers and for training purposes,” this methodology opens new possibilities for technique refinement and performance optimization. For sprint kayakers and canoeists, the principles discovered in rowing research offer valuable insights into the hydrodynamic forces at play in all paddle sports. The fundamental understanding that efficiency varies throughout each stroke cycle, depends on velocity, and can be objectively measured provides a foundation for more scientific approaches to training and equipment selection across all paddle sport disciplines.

Source: Affeld, K., Schichl, K., & Ziemann, A. (1993). Assessment of Rowing Efficiency. International Journal of Sports Medicine, 14(Suppl 1), S39-S41.