Recent groundbreaking research from École polytechnique and Phyling, led by Romain Labbé and his team, has revolutionized our understanding of paddle optimization in water sports. Their study “Physics of rowing oars” challenges conventional wisdom by examining paddle efficiency through the lens of human physiological constraints rather than purely mechanical considerations. This research doesn’t just apply to rowing—its insights extend to sprint kayaking and canoeing, offering valuable guidance for any athlete who depends on paddle efficiency for performance.

Understanding the Fundamental Physics of Paddle Propulsion

The relationship between paddle dimensions and performance is far more complex than most athletes realize. When you pull your paddle through the water, you’re engaging with two distinct physical forces that determine your efficiency. The first is pressure drag, which occurs when your blade pushes against the water’s resistance. The second is added mass, which represents the additional water that gets accelerated along with your blade during each stroke.

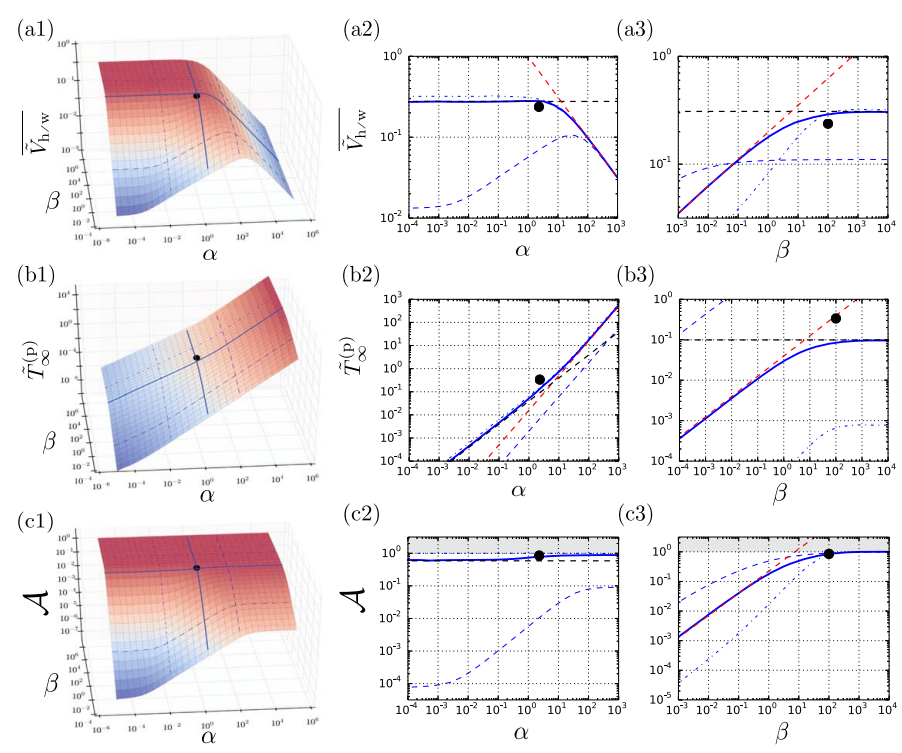

The researchers discovered that “real rowing lies at the cross-over between these two regimes,” meaning that competitive paddle sports operate precisely at the intersection where both forces matter equally. This finding explains why paddle design has evolved so dramatically over the past century and why there isn’t a one-size-fits-all solution for optimal paddle dimensions.

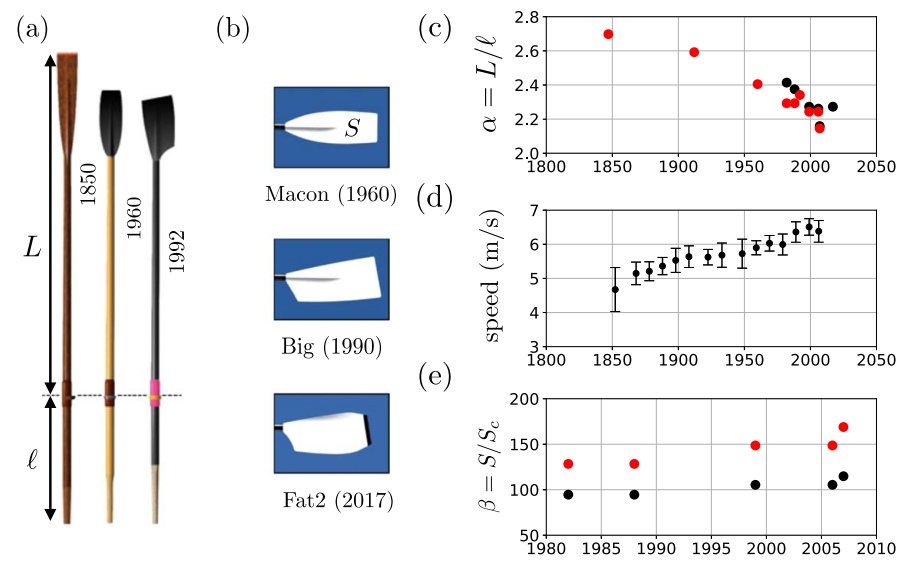

Figure 2 from the cited paper: Evolution of rowing oar design showing (a) historical oar lengths, (b) blade designs from Macon (1960) to Fat2 (2017), (c) aspect ratio evolution, (d) performance improvements over time, and (e) dimensionless blade area changes.

Figure 2 from the cited paper: Evolution of rowing oar design showing (a) historical oar lengths, (b) blade designs from Macon (1960) to Fat2 (2017), (c) aspect ratio evolution, (d) performance improvements over time, and (e) dimensionless blade area changes.

The study introduces a crucial concept called “anchoring,” which measures how effectively your paddle transfers energy to move your boat forward rather than simply slipping through the water. “If anchoring equals 1, the blade does not move with respect to the water and all the rower’s energy is transferred to the boat. In contrast, if anchoring equals 0 the boat does not move and the oars slip in the water.” This anchoring efficiency directly correlates with the ratio between your paddle’s outboard length (the part in the water) and inboard length (the part you hold), known as the aspect ratio.

To validate their theoretical framework, the researchers built a sophisticated rowing robot that could maintain constant force throughout each stroke—something human athletes cannot achieve due to natural variations in muscle output. Their experiments revealed that “when increasing α [the aspect ratio], the average hull velocity decreases, coherent with an increase in the propulsive stroke duration.” This finding has profound implications for how athletes should select their equipment based on their individual strengths and competitive goals.

Strategic Implications: Sprint Power vs Endurance Efficiency

The research reveals a fundamental trade-off that every competitive paddler faces: optimizing for raw speed versus energy efficiency. This distinction becomes critical when choosing between sprint and endurance racing strategies, as each demands different paddle characteristics to maximize performance.

For sprint-oriented athletes seeking maximum velocity regardless of energy expenditure, the study suggests using shorter paddles with larger blades. “If one wants to achieve maximum velocity regardless of injected energy—or equivalently mean power—(sprint strategy), one should choose rather short oars α ∼ 1.” However, this approach comes with a physiological cost: shorter paddles require higher stroke rates, which “might be hard to achieve from a physiological point of view, by that setting a lower bound to α.”

Conversely, endurance athletes benefit from a different approach. “If one is rather tempted by maximal efficiency (endurance race), then long oars are indicated in order to reduce the mean power provided by the rower.” This strategy allows athletes to maintain sustainable power output over longer distances while maximizing the energy transfer efficiency from their muscles to forward propulsion.

The historical evolution of competitive rowing equipment supports these findings. Over the past 170 years, oar lengths have decreased by almost 25% while blade areas have increased significantly. This evolution reflects the sport’s shift toward sprint-oriented competition formats, where races typically last around six minutes—firmly in the sprint regime rather than true endurance events.

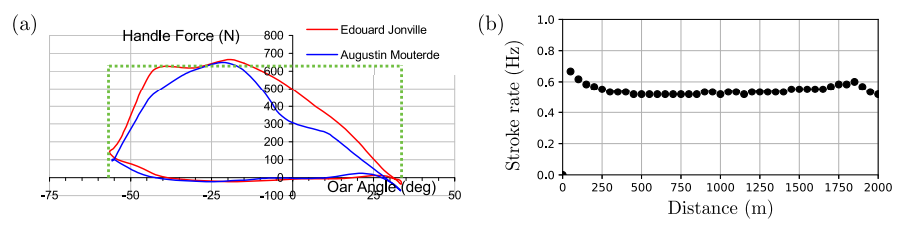

Figure 3 from the cited paper: (a) Handle force profiles during rowing strokes from elite French rowers, and (b) stroke frequency consistency during the 2016 Lucerne World Championship M1x final.

Figure 3 from the cited paper: (a) Handle force profiles during rowing strokes from elite French rowers, and (b) stroke frequency consistency during the 2016 Lucerne World Championship M1x final.

The research also reveals why stroke rate matters so much in paddle sports. The relationship between paddle dimensions and optimal stroke frequency isn’t arbitrary—it’s governed by fundamental physics. Athletes using shorter paddles naturally achieve higher stroke rates because less energy is lost to water slip during each stroke cycle. This explains why kayakers, who typically use paddles with an aspect ratio of 1 (no mechanical advantage from a fulcrum), maintain stroke rates near 100 strokes per minute compared to rowers’ 30-40 strokes per minute.

Practical Applications Across Paddle Sports

While this research focused specifically on rowing, its principles apply broadly across paddle sports, with important modifications for different disciplines. In sprint kayaking and canoeing, where athletes don’t benefit from the mechanical advantage of a rowlock fulcrum, the physics still govern the relationship between blade dimensions, stroke rate, and efficiency.

The study notes that “in kayaking, as there is no rowlock, α = 1, and the stroke frequency observed in competitions is much higher than that of rowing (near 100 strokes per minute), which follows the tendency that the stroke frequency decreases with α.” This fundamental difference explains why kayak paddles are designed so differently from rowing oars and why kayaking technique emphasizes rapid, efficient strokes rather than the longer, more powerful strokes seen in rowing.

For sprint kayakers and canoeists, the research suggests that blade design becomes even more critical since you can’t adjust the mechanical advantage through length ratios. “Kayak blades have another specific feature: they are very hollow to increase added mass.” This design choice maximizes the anchoring effect by ensuring more water moves with each paddle stroke, even though the stroke frequency is much higher.

The researchers’ robot testing revealed specific force profiles that athletes can use to evaluate their own technique. Elite rowers typically generate maximum handle forces around 700 N during peak stroke phases, with relatively consistent force application throughout each stroke. Understanding these force patterns helps athletes optimize their paddle selection based on their individual strength capabilities and race distance requirements.

Figure 7 from the cited paper: Master plots showing (a) rescaled mean boat velocity, (b) propulsive stroke duration, and (c) anchoring efficiency as functions of aspect ratio α and dimensionless blade area β, with asymptotic behaviors and real boat data points.

Figure 7 from the cited paper: Master plots showing (a) rescaled mean boat velocity, (b) propulsive stroke duration, and (c) anchoring efficiency as functions of aspect ratio α and dimensionless blade area β, with asymptotic behaviors and real boat data points.

The study’s most practical contribution may be its framework for individualized paddle optimization. Rather than relying on traditional equipment selection based on athlete height or weight categories, this research provides a physics-based approach that considers individual strength profiles, racing distances, and physiological constraints. “The optimal oar length and blade size depend on the adopted strategy” and should be selected based on whether an athlete prioritizes maximum speed or sustainable efficiency.

For coaches and athletes, this research provides concrete guidance: measure your maximum sustainable force output, determine your optimal stroke rate for your target race distance, and then select paddle dimensions that maximize either speed (for sprint events) or efficiency (for longer races) within your physiological limits. The days of one-size-fits-all paddle selection are ending, replaced by individualized optimization based on solid physics principles.

Reference: Labbé, R., Boucher, J. P., Clanet, C., & Benzaquen, M. (2019). Physics of rowing oars. New Journal of Physics, 21(9), 093050. https://doi.org/10.1088/1367-2630/ab4226